All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Spiritual Fortitude as a Mediator between Grit and Flourishing among Adolescent Victims of Bullying

Abstract

Introduction

Bullying in Indonesian schools remains a significant issue, affecting approximately 41% of students. Victims often experience severe psychological consequences, including depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, which hinder their ability to flourish. Flourishing refers to a state of well-being characterized by positive emotions, meaning, and strong relationships. Previous studies suggest that grit—defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals—can promote flourishing. However, grit alone may not fully explain well-being outcomes, indicating the need to explore additional psychological factors, such as spiritual fortitude.

Methods

This study employed a quantitative survey design with convenience sampling. A total of 1,215 Indonesian adolescents (aged 15–23) participated in this study, but only 1,140 had experienced bullying; therefore, only these 1,140 participants were included in the inferential statistical analysis. They completed validated instruments measuring grit, flourishing, and spiritual fortitude. Structural Equation Modeling (SmartPLS) was used to analyze mediation effects and test the study’s hypotheses.

Results

The findings supported all three hypotheses: (1) grit significantly predicts flourishing (β = 0.270, p < 0.001), (2) spiritual fortitude positively influences flourishing (β = 0.509, p < 0.001), and (3) spiritual fortitude mediates the relationship between grit and flourishing (β = 0.317, p < 0.001). The results indicate that while grit contributes to flourishing, spiritual fortitude enhances this relationship, providing additional psychological resilience. Furthermore, the direct predictive effect of grit on flourishing remained statistically significant even when spiritual fortitude was included as a mediator in the model.

Discussion

These results highlight that while grit contributes to adolescent flourishing, spiritual fortitude amplifies this effect by providing inner strength rooted in meaning and resilience. The findings emphasize the cultural relevance of spiritual resources in Indonesia and support the integration of spiritual development in psychological interventions.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the importance of both perseverance and spiritual strength in helping adolescent victims of bullying achieve flourishing. Interventions aimed at fostering grit and spiritual fortitude could support adolescent mental health recovery. This study provides implications for educational and mental health policies to promote flourishing in trauma-affected populations.

1. INTRODUCTION

Bullying among Indonesian adolescents remains a serious and persistent problem despite the existence of multiple national laws and child protection policies. As Wuryaningsih et al. [1] pointed out, implementation gaps and low awareness across schools and communities contribute to the continuation of bullying behaviors. Cultural and social factors, particularly in collectivist societies like Indonesia, can normalize bullying behaviors as part of maintaining group conformity and social control. Peer pressure and hierarchical norms, as noted by Supriyadi and Sudrajat [2], often reinforce these actions by discouraging individual resistance. Studies by Hidayati and Amalia [3] and Gusti Ngurah Edi Putra et al. [4] found that bullying in adolescence is strongly linked to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and even suicidal ideation, highlighting the severity of its psychological toll. Over time, this can lead to diminished self-esteem and even chronic mental health conditions if not properly addressed [5]. Mental health problems are often indicators of underlying issues with psychological well-being, which in turn signal challenges in flourishing.

In this study, bullying is defined in a broad and retrospective manner, encompassing various forms of victimization that may have occurred in the past. As described by Olweus [6], bullying typically involves repetitive and intentional aggression across various forms. Sigurdson et al. [7] further emphasize that even bullying reported retrospectively can predict long-term mental health difficulties into adulthood. Such lingering effects can significantly hinder psychological development and, more specifically, an individual’s ability to achieve a state of flourishing. Therefore, understanding how past bullying experiences relate to current flourishing is crucial for addressing long-term mental health outcomes.

Flourishing is not merely the absence of mental illness but rather a state of thriving where individuals experience positive emotions, meaning, engagement, and strong relationships. According to research by Huppert and So [8], flourishing encompasses high levels of well-being, involving both feeling good and functioning effectively in life. This concept is crucial because when psychological well-being is compromised, it affects an individual's ability to flourish, leading to issues such as decreased life satisfaction and impaired functioning [9, 10]. Moreover, flourishing includes eudaimonic elements, such as meaning and purpose, which are critical for long-term mental health. If these aspects are hindered, they can manifest in mental health disorders, affecting one's ability to maintain healthy social relationships and life satisfaction [11].

Adolescent victims of bullying often face significant disruptions in their psychological well-being, making it difficult for them to achieve a flourishing state. Flourishing, which involves a balance of positive emotions, meaningful engagement, and strong social connections, can be severely affected by the trauma associated with bullying. According to Hong et al. [12] and Rey et al. [13], adolescent bullying victims show increased levels of emotional distress across multiple countries, reinforcing its global psychological burden. Moreover, the negative mental health outcomes often include social withdrawal and lower life satisfaction, which are critical components of flourishing [14]. The relationship between flourishing and mental health in these adolescents is complex, as those with low levels of flourishing are more vulnerable to mental health disorders and suicidal behavior. Guo et al. [14] and Oh et al. [15] suggest that targeted interventions—such as building emotional regulation and supportive environments—can buffer against the negative impacts of bullying on flourishing and mental health.

Grit, according to Duckworth et al. [16], is characterized by persistence and passion for long-term goals, and can be seen by researchers as a promising solution for improving flourishing among adolescent victims of bullying in Indonesia. Adolescents who develop grit are better equipped to handle the psychological challenges posed by bullying, as it helps them stay committed to overcoming adversity. Research has shown that individuals with higher levels of grit demonstrate better resilience, which supports their emotional recovery from traumatic experiences like bullying [17, 18]. This ability to maintain focus on long-term goals, even in the face of stress, enables bullying victims to regain a sense of control and improve their mental well-being [19]. Additionally, grit has been linked to positive mental health outcomes such as reduced anxiety and depression, key factors in achieving a flourishing state. When adolescents apply grit, they are more likely to engage in healthy coping mechanisms, promoting their resilience and helping them rebuild self-esteem and social connections [20]. These improvements contribute to long-term psychological flourishing, even after the negative experiences of bullying.

According to Duckworth et al. [16], grit consists of two core dimensions: consistency of interest and perseverance of effort. Consistency of interest refers to the ability to maintain long-term focus and sustained passion toward one’s goals, even when external rewards or immediate changes are lacking. Individuals with high consistency are less likely to change directions frequently and tend to stay committed to what they care about. Perseverance of effort, on the other hand, refers to the tendency to work hard and persist in the face of setbacks, obstacles, or failure. It reflects an individual’s determination to continue striving despite adversity. While both dimensions play a vital role in promoting psychological resilience, grit as a whole may not be sufficient on its own to fully foster flourishing. Other psychological strengths may be required to complement grit and deepen its impact, particularly in the context of trauma recovery.

Although grit is often seen as a strong predictor of flourishing, its role remains somewhat unclear. Research suggests that grit—defined as perseverance and passion for long-term goals—does not always guarantee flourishing, as other factors may influence the outcome. For instance, grit alone may not fully explain well-being, as emotional regulation and other mediators can also play critical roles in shaping psychological outcomes [21, 22]. One potential mediator to consider is spiritual fortitude, which involves the ability to endure adversity through inner strength and spiritual beliefs. Studies indicate that spiritual fortitude may provide the emotional and mental resilience needed to transform challenging experiences into growth, thus supporting flourishing [21, 23]. By combining grit with spiritual fortitude, individuals could develop a more holistic approach to overcoming adversities such as bullying, fostering both perseverance and deeper emotional resilience [23, 24].

Spiritual fortitude, which refers to the strength derived from spiritual beliefs and practices, plays a significant role in personal resilience [25], particularly within Indonesia's cultural and religious context. Indonesia's predominantly Muslim population, alongside communities of other faiths, often draws upon spiritual resources to cope with life's challenges. For adolescents facing adversity such as bullying, spiritual fortitude can serve as a crucial buffer, offering them inner strength to overcome psychological distress. This fortitude is rooted in religious teachings that promote patience, perseverance, and reliance on a higher power, making it relevant for fostering resilience across different religious groups in Indonesia [26, 27].

While emotional regulation and perceived social support are commonly studied mediators in the flourishing process, spiritual fortitude was prioritized in this study due to its growing empirical support in contexts involving existential adversity. Spiritual fortitude offers a unique resilience pathway that is particularly relevant in cultural settings where spiritual beliefs are deeply embedded, such as Indonesia [25, 28]. Unlike emotional regulation, which focuses on cognitive coping, or social support, which relies on external resources, spiritual fortitude emphasizes internal, meaning-driven endurance—making it especially significant for adolescents facing chronic adversity like bullying.

According to the previous research and phenomena in Indonesia regarding bullying, the objective of this study is to investigate the role of spiritual fortitude as a mediator of grit influence on flourishing among Indonesian adolescents, particularly in dealing with challenges such as bullying. It aims to explore how spiritual fortitude strengthens the relationship between grit and flourishing. Furthermore, the study seeks to identify the practical implications of spiritual fortitude for educational policy and mental health interventions in Indonesia, providing better support for adolescents in overcoming psychological issues.

This study contributes to the existing literature in several ways. Conceptually, it introduces spiritual fortitude as a mediator in a context of bullying, extending prior models of psychological resilience. Methodologically, it employs a robust SEM approach using SmartPLS with a large, diverse sample of Indonesian adolescents. Culturally, the study addresses a gap by highlighting the role of spiritual strength in a non-Western context, thereby offering new insights for culturally sensitive mental health interventions.

The hypotheses in this research are as follows:

- H1: Grit is proven to significantly predict flourishing in adolescent victims of bullying in Indonesia.

- H2: Spiritual fortitude is proven to significantly predict flourishing in adolescent victims of bullying in Indonesia.

- H3: Spiritual fortitude can act as a mediator in the influence of grit on flourishing in adolescent victims of bullying in Indonesia.

2. METHOD

This study employed a quantitative approach, utilizing a survey research design that included a rating scale question in the form of a questionnaire. The type of sampling used in this research is convenience sampling. The sample criteria used in this study were adolescents aged 15–23 years who were studying in Indonesia and had experienced bullying in their life. In this study, screening questions were presented to see whether the respondents had experienced bullying. There are 5 types of bullying experiences used as screening statements, and respondents could answer yes or no to whether or not they had experienced bullying in their lives. The following are the five statements [1]: A friend says something mean and hurtful to you (verbal bullying) [2]. Being ignored, ostracized, or abandoned by your friends (social bullying) [3]. A friend kicks, hits, or pushes and threatens you (physical bullying) [4]. The spread of fake news about you so that your friends don't like you (verbal bullying) [5]. Other cruel and hurtful treatment towards you (physical bullying). If the respondent answered “no” to all five statements of bullying experiences, then he/she cannot be a respondent in this study. If he/she responded to one of the statements by answering yes, then he/she can be classified according to one of the statements they responded to as the type of bullying victim experiences (either verbal, physical, or social bullying). If he/she responded to more than one statement by answering yes, then he/she is accordingly classified according to the statement they responded to as their type of bullying victim experiences (either as verbal and physical, social and physical, verbal and social, or all types of bullying). These five screening items were developed based on the conceptual framework of bullying established by Olweus (1993), covering verbal, physical, and social forms of victimization. Although no formal psychometric validation was conducted for these dichotomous items, content validity was established through expert judgment by psychologists specializing in adolescent development and school-based bullying. Each item was reviewed for cultural relevance and clarity in the Indonesian context. Due to their categorical nature and distinct content domains, internal consistency metrics (e.g., Cronbach’s alpha) were not applied.

2.1. Participants

The study involved 1,215 participants, with the majority being female (859 participants, 70.7%). A significant portion of the respondents had attained higher education, with 526 individuals (43.3%) holding college degrees. Additionally, 690 participants (56.8%) were identified as Protestant Christians. The largest age group in the study consisted of those between 15 and 17 years old, accounting for 682 participants (56.1%). For experiences of bullying, most of the participants answered that the bullying experiences they experienced were between ages 5 and 10 years old (53.3%), and the types of bullying they experienced were mostly a combination of social and physical bullying (31.5%). Of the 1,215 participants, there were 75 participants who reported that they did not experience bullying.

Participants were eligible to participate in this study if they met the following criteria [1]: aged between 15 to 23 years [2]; currently enrolled in a school or university in Indonesia; and [3] had experienced at least one form of bullying (verbal, physical, or social). Participants who responded “no” to all five bullying screening items were excluded from inferential statistical analysis. Although the age criterion was 15 to 23 years, students older than 23 were still considered eligible as long as they were actively enrolled in a university in Indonesia at the time of data collection.

Participants who reported no history of bullying (n = 75) were excluded from all inferential statistical analyses, including the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) procedures. These respondents were only included in basic descriptive comparisons to provide contextual insight into differences between bullied and non-bullied adolescents. For all hypothesis testing and model estimations, the final analytic sample consisted solely of participants who had experienced at least one form of bullying (n = 1,140). This exclusion ensured that the inferential findings were accurately focused on the population of interest—adolescents with bullying experiences.

The sample size of 1,140 participants was determined based on previous studies using structural equation modeling (SEM) approaches, which recommend a minimum sample size of 10 times the number of structural paths in the most complex model to ensure robust estimation and model stability. Given the complexity of the mediation model in this study, this sample size was deemed sufficient to achieve adequate statistical power. Additionally, a larger sample helps reduce sampling bias and increases the generalizability of the findings to the broader adolescent population in Indonesia.

Participants were recruited using convenience sampling through digital survey distribution on school networks, youth communities, and university platforms. While this non-probabilistic method facilitated wide data collection from various regions, it may introduce selection bias. To mitigate this risk, demographic monitoring was conducted throughout the recruitment process to ensure diversity across age, gender, education level, and religious affiliation. Additionally, screening criteria ensured that only adolescents with confirmed bullying experiences were included in inferential analyses. However, as no randomization or stratification was applied, the generalizability of the findings remains limited to similar populations. The demographic data can be seen in Table 1.

2.2. Measures

The research utilized three primary measurement instruments to assess the variables of flourishing, grit, and spiritual fortitude.

1. Flourishing was measured using the Flourishing Scale (FS), an 8-item instrument designed to capture respondents' perceptions of their success in key areas such as relationships, purpose, and self-esteem [29]. Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from Strongly Disagree [1] to Strongly Agree [5]. The scale has demonstrated strong reliability and validity in prior research.

2. Grit was assessed using the Grit Scale, developed by Duckworth et al. [16]. This scale consists of 12 items divided into two subscales: consistency of interests and perseverance of effort. Each item is scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (Not at all like me) to 5 (Very much like me). The scale has shown high reliability and is predictive of long-term success across different contexts.

3. Spiritual Fortitude was evaluated using the Spiritual Fortitude Scale (SFS-9), a 9-item measure focusing on three dimensions: spiritual endurance, spiritual enterprise, and redemptive purpose [28]. Responses were rated on a Likert scale and the scale has demonstrated strong psychometric properties in studies of adversity and spiritual well-being.

| Characteristics | Number (N) | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | - | - |

| Male | 356 | 29.3 |

| Female | 859 | 70.7 |

| Education Level | - | - |

| High School, Grade 10 | 205 | 16.9 |

| High School, Grade 11 | 155 | 12.8 |

| High School, Grade 12 | 329 | 27.1 |

| College/University | 526 | 43.3 |

| Religion | - | - |

| Protestant Christian | 690 | 56.8 |

| Catholic | 218 | 17.9 |

| Islam | 166 | 13.7 |

| Buddhist | 123 | 10.1 |

| Confucianism | 12 | 1.0 |

| Hindu | 3 | 0.2 |

| Other Beliefs | 3 | 0.2 |

| Age Group | - | - |

| 15-17 years | 682 | 56.1 |

| 18-20 years | 429 | 35.3 |

| 21-23 years | 89 | 7.3 |

| Over 23 years | 15 | 1.2 |

| Types of Bullying | - | - |

| No Type of Bullying | 75 | 6.2 |

| Verbal | 91 | 7.5 |

| Social | 176 | 14.5 |

| Physical | 69 | 5.7 |

| Verbal+Social | 173 | 14.2 |

| Verbal+Physical | 179 | 14.7 |

| Social+Physical | 383 | 31.5 |

| All Types of Bullying | 69 | 5.7 |

| Bullying Event | - | - |

| Never Experienced | 75 | 6.2 |

| Never Experienced | 647 | 53.3 |

| Never Experienced | 390 | 32.1 |

| More than Age 15 | 103 | 8.5 |

These instruments were chosen due to their proven reliability and relevance to the constructs being examined, ensuring robust measurement of psychological resilience, long-term perseverance, and spiritual endurance.

The reliability and validity analysis of the field data demonstrates solid psychometric properties across the various constructs. Cronbach's alpha values for all scales exceed the acceptable threshold of 0.7, indicating good internal consistency. Specifically, Spiritual Fortitude shows the highest reliability with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.876, while Consistency of Interest has the lowest but still acceptable value at 0.702. Composite reliability (rho_c) further confirms the strong reliability, with values ranging from 0.816 to 0.901, suggesting that the scales consistently measure their respective constructs.

In terms of validity, the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values indicate adequate convergent validity for most constructs, with all values exceeding the 0.5 threshold, meaning that more than 50% of the variance is explained by the constructs. Grit and Perseverance of Effort show the highest AVE at 0.557, followed by Consistency of Interest (0.525), while Spiritual Fortitude has the lowest AVE (0.506), which still meets the recommended minimum level for valid constructs.

Overall, the results confirm that the measurement tools used in this study are both reliable and valid for assessing the constructs of interest. The construct reliability and validity can be seen in Table 2.

| - | C. alpha | C.R. rho-c | AVE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency of Interest (Grit Dimension) | 0.702 | 0.816 | 0.525 |

| Perseverance of Effort (Grit Dimension) | 0.732 | 0.833 | 0.557 |

| Grit (Total Score) | 0.732 | 0.833 | 0.557 |

| Flourishing | 0.810 | 0.863 | 0.513 |

| Spiritual Fortitude | 0.876 | 0.901 | 0.506 |

2.3. Procedure

The data collection procedure began with an expert judgment phase, where three measurement instruments were assessed by field experts to ensure that the translation and adaptation into the Indonesian language were accurate and culturally appropriate. Once the instruments were confirmed to meet these standards, a tryout was conducted involving 43 respondents to assess reliability. The tryout sample consisted of high school and early college students aged 15 to 23 years, with a fairly balanced gender distribution (53% female, 47% male). Participants were recruited from two educational institutions in urban areas and had diverse religious backgrounds, reflecting the general characteristics of the target population. The results demonstrated satisfactory internal consistency for all scales. The overall Grit scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.826, with its sub-dimensions—Perseverance of Effort and Consistency of Interest —achieving reliability coefficients of 0.843 and 0.770, respectively. The Spiritual Fortitude Scale showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.798, while the Flourishing Scale achieved a reliability score of 0.829. These findings confirm that all instruments possess adequate psychometric properties for use in the main study. After confirming the reliability, data collection was carried out on the research sample.

Although the standard back-translation procedure was not implemented, all instruments were evaluated through expert judgment by bilingual professionals in psychology and language translation to ensure semantic, conceptual, and cultural equivalence. Additionally, a preliminary tryout was conducted, and the results demonstrated acceptable levels of reliability. The Cronbach’s alpha values across the instruments confirmed good internal consistency, supporting the adequacy of the translated measures for this study.

2.4. Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of Universitas Pelita Harapan, Indonesia (Approval No. 143/LPPM-UPH/VII/2024). All participants provided informed consent prior to their involvement in the study. For participants under the age of 18, written consent was also obtained from their parents or legal guardians.

2.5. Human and Animal Guidelines

This study involving human subjects was conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration to ensure ethical research practices and the protection of participants' rights.

2.6. Data Analyses

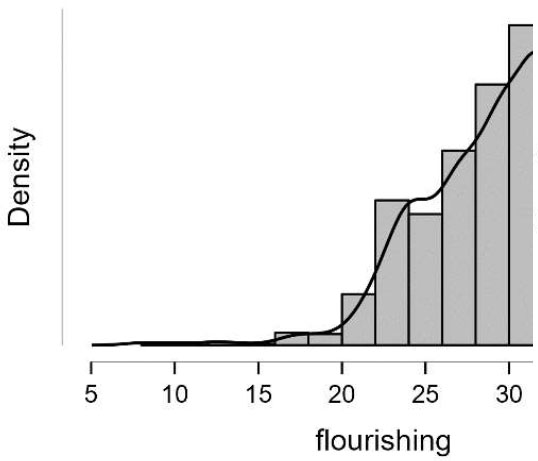

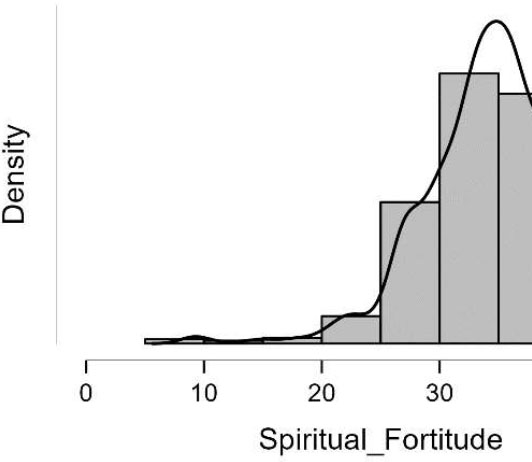

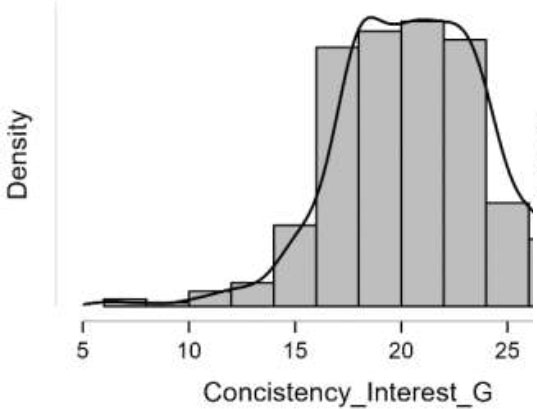

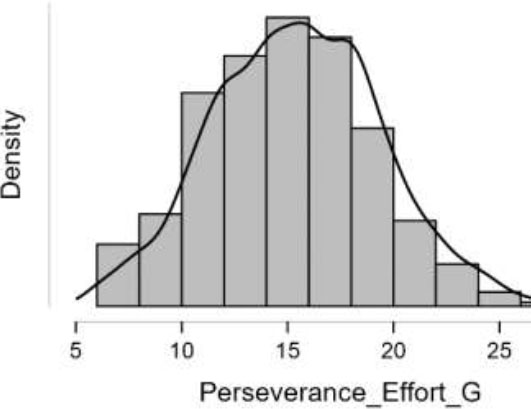

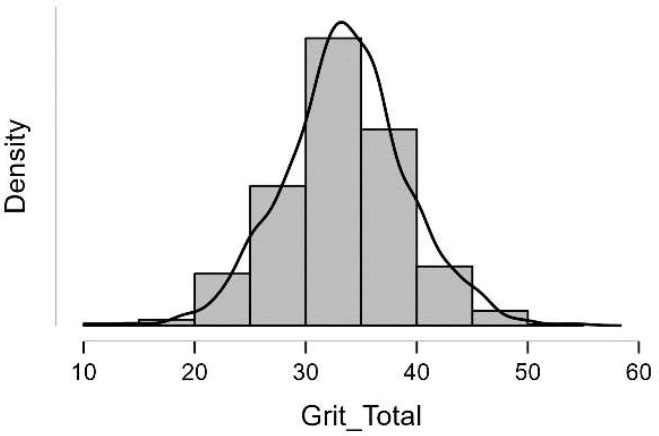

Data were analyzed using Smart PLS due to the non-normal distribution of the collected data, which precluded the use of AMOS. Smart PLS was chosen because it is robust for analyzing data with non-normal distribution and supports complex structural equation modeling. The descriptive analysis showing skewness, kurtosis, and p-value of Shapiro Wilk showing abnormal distribution can be seen in Table 3.

| - | Flourishing | Spiritual-Fortitude | Consistency-Interest | Perseverance Effort | Grit-Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 29.90 | 34.54 | 20.84 | 15.49 | 33.57 |

| Std. Dev. | 4.73 | 5.77 | 3.72 | 3.99 | 5.57 |

| Skew | -0.47 | -0.69 | -0.16 | 0.15 | 0.01 |

| SE Skew | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| Kurtosis | 0.64 | 1.57 | 0.70 | -0.04 | 0.54 |

| SE Kurtosis | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 | 0.14 |

| Shapiro-Wilk | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 0.99 | 0.99 |

| P- Shapiro-Wilk | 4.15×10-12 | 1.15×10-15 | 5.54×10-10 | 3.65×10-6 | 6.57×10-5 |

| Minimum | 8.00 | 9.00 | 6.00 | 6.00 | 12.00 |

| Maximum | 39.00 | 45.00 | 30.00 | 30.00 | 55.00 |

Before conducting inferential analyses, data were screened for completeness. Respondents with missing values on key variables required for Structural Equation Modeling were excluded using listwise deletion. The overall percentage of missing data was minimal (less than 5% across all measured constructs), and no imputation techniques were applied. Given the large sample size and low level of missingness, complete-case analysis was deemed appropriate and unlikely to bias the results.

As illustrated in the distribution plot and the descriptive analysis results, the data for the Flourishing (Fig. 1)—and likewise for the other main variables, including Spiritual Fortitude (Fig. 2), Consistency of Interest (Fig. 3), Perseverance of Effort (Fig. 4) and Overall Grit Total Score (Fig. 5)—do not exhibit normal distribution characteristics. This conclusion is supported by several statistical indicators: the Shapiro-Wilk tests yielded highly significant p-values (p < 0.001), indicating a departure from normality; the skewness and kurtosis values fall outside the range typically associated with normal distributions; and the visual inspection of distribution plots also confirms non-normal patterns across all variables. Given these distributional properties, the use of covariance-based SEM (e.g., AMOS) was deemed inappropriate. Instead, this study employed Smart PLS, a variance-based SEM approach that is robust to non-normal data and more suitable for exploratory and complex mediation models under these conditions.

The analysis began by evaluating the model fit through several key indicators, such as the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), to ensure that the model was a good fit for the data. Next, reliability and validity tests were performed, including assessing Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability, and the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) for each construct. After ensuring the measurement model was satisfactory, path analysis was conducted to examine the relationships between variables, including the mediation effect of spiritual fortitude on the relationship between grit and flourishing. The mediation effects were tested using bootstrapping procedures with 5,000 resamples at a 95% confidence interval. This non-parametric approach was used to assess the significance of indirect effects, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05.

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait ratio (HTMT), which is considered a more sensitive method than traditional techniques such as the Fornell-Larcker criterion. Although VIF is often used to assess multi-collinearity, HTMT was prioritized in this study as a robust alternative for evaluating discriminant validity among constructs in the measurement model. All HTMT values in this study were below the conservative threshold of 0.85, indicating satisfactory discriminant validity across constructs [30]. For example, the HTMT values for Flourishing –Consistency of Interest (0.163), Grit–Flourishing (0.724), and Spiritual Fortitude–Perseverance of Effort (0.755) confirmed that these constructs are conceptually distinct. Therefore, no issues of multicollinearity or overlapping constructs were present in the measurement model. Full results of HTMT analysis can be seen in Table 4.

The predictive values of the grit subscales were assessed within a structural equation model using SmartPLS. Rather than employing simple linear regression for each subscale, this study utilized path analysis to examine direct and indirect effects simultaneously within a comprehensive model. This approach enabled the evaluation of the distinct contributions of both consistency of interest and perseverance of effort while accounting for the mediating role of spiritual fortitude.

Distribution plot for flourishing.

Distribution plot for spiritual fortitude.

Distribution plot for consistency of interest.

Distribution plot for perseverance effort.

Distribution plot for overall grit total score.

| - | Original Sample (O) |

|---|---|

| Flourishing <-> Consistency of Interest | 0,163 |

| Grit <-> Consistency of Interest | 0,306 |

| Grit <-> Flourishing | 0,724 |

| Perseverance of Effort <-> Consistency of Interest | 0,278 |

| Perseverance of Effort <-> Flourishing | 0,730 |

| Perseverance of Effort <-> Grit | 1,270 |

| Spiritual Fortitude <-> Consistency of Interest | 0,126 |

| Spiritual Fortitude <-> Flourishing | 0,766 |

| Spiritual Fortitude <-> Grit | 0,760 |

| Spiritual Fortitude <-> Perseverance of Effort | 0,755 |

3. RESULTS

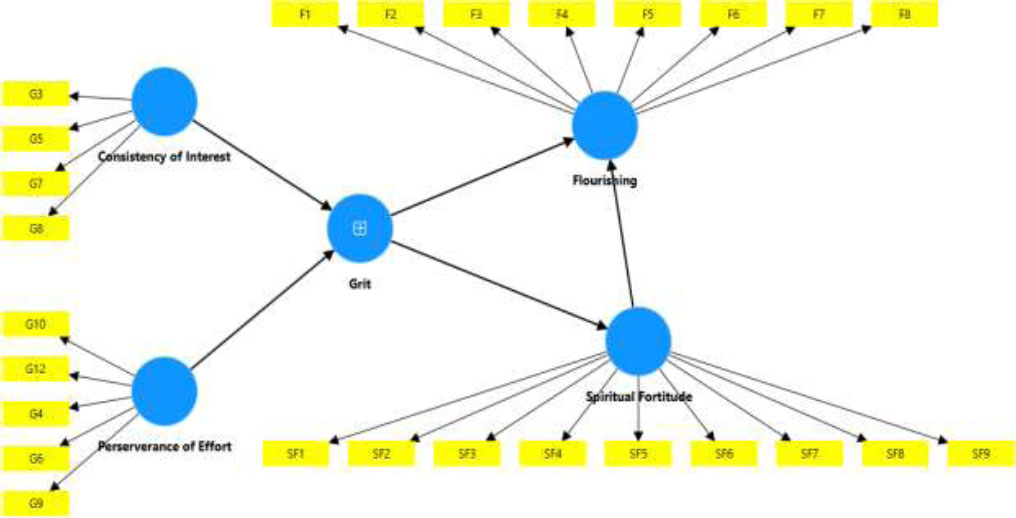

The results of the Smart PLS model can be seen in Fig. (6).

The Smart PLS analysis provided insights into the relationships between grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing, supporting all the proposed hypotheses. The path coefficients can be seen in Table 5.

| - | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency of Interest -> Grit | 0,016 | 0,005 | 3,189 | 0,001 |

| Grit -> Flourishing | 0,270 | 0,031 | 8,823 | 0,000 |

| Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude | 0,625 | 0,021 | 29,118 | 0,000 |

| Perserverance of Effort -> Grit | 0,983 | 0,001 | 665,302 | 0,000 |

| Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing | 0,509 | 0,032 | 15,873 | 0,000 |

3.1. Path Coefficients

The structural model demonstrated that grit has a significant positive effect on flourishing (β = 0.271, t = 8.823, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 1 (H1). This finding suggests that adolescents with higher levels of grit, characterized by persistence and passion for long-term goals, tend to flourish more despite facing adversity, such as bullying. Additionally, spiritual fortitude was found to be a significant predictor of flourishing (β = 0.508, t = 15.873, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2 (H2). Adolescents who draw upon their spiritual beliefs for strength are more likely to achieve psychological and emotional well-being, even in challenging circumstances.

The analysis also confirmed the mediating role of spiritual fortitude in the relationship between grit and flourishing (β = 0.508, t = 15.873, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 3 (H3). Specifically, grit significantly predicted spiritual fortitude (β = 0.624, t = 29.118, p < 0.001), and spiritual fortitude, in turn, had a significant positive effect on flourishing. This mediation pathway suggests that spiritual fortitude enhances the positive influence of grit on flourishing, offering adolescents an inner strength that helps them thrive despite their bullying experiences.

3.2. Sub-Dimensions of Grit

The analysis also explored the two dimensions of grit—Consistency of Interest and Perseverance of Effort. The relationship between Consistency of Interest and overall grit was significant (β = 0.016, t = 3.189, p = 0.001), as was the relationship between Perseverance of Effort and overall grit (β = 0.983, t = 665.302, p < 0.001). This indicates that perseverance plays a much stronger role in shaping grit than consistency of interest.

3.3. Model Fit

The model fit indices indicated that the structural model fit the data well. The Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.074 for the estimated model and 0.073 for the saturated model, both values below the threshold of 0.08, indicating a good fit. Additionally, the d_ULS values for the estimated model (2.520) and the saturated model (2.468) were within acceptable limits, further confirming the model's fit.

Smart PLS model.

3.4. Bootstrapping Results and Specific Indirect Effects

The bootstrapping analysis with 5,000 resamples confirmed the significance of both direct and indirect effects, highlighting a partial mediation effect of spiritual fortitude. The direct effect of grit on flourishing remained significant (β = 0.317, t = 13.614, p < 0.001), even when the indirect effect through spiritual fortitude was accounted for. This indicates that spiritual fortitude partially mediates the relationship between grit and flourishing rather than fully explaining it.

In addition to the main mediation model, several specific indirect effects were examined:

3.4.1. Consistency of Interest -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude

The indirect effect of Consistency of Interest on Spiritual Fortitude through Grit was significant (β = 0.010, t = 3.155, p = 0.002), indicating that consistency of interest in long-term goals has a small but meaningful contribution to the development of spiritual fortitude via its effect on grit.

3.4.2. Perseverance of Effort -> Grit -> Flourishing

The indirect effect of Perseverance of Effort on Flourishing via Grit was significant (β = 0.266, t = 8.826, p < 0.001), demonstrating that perseverance of effort strongly contributes to flourishing when mediated by grit.

3.4.3. Perseverance of Effort -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing

The indirect pathway from Perseverance of Effort to Flourishing via Grit and Spiritual Fortitude was also significant (β = 0.312, t = 13.623, p < 0.001), confirming that spiritual fortitude amplifies the effect of perseverance of effort on flourishing.

3.4.4. Perseverance of Effort -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude

The indirect effect of Perseverance of Effort on Spiritual Fortitude through Grit was highly significant (β = 0.614, t = 29.049, p < 0.001), underscoring the strong relationship between the perseverance of effort and spiritual fortitude, with grit serving as a key intermediary.

3.4.5. Consistency of Interest -> Grit -> Flourishing

The indirect effect of Consistency of Interest on Flourishing via Grit was smaller but still significant (β = 0.004, t = 3.005, p = 0.003), suggesting that while consistency of interest is not as strong a predictor as perseverance of effort, it still contributes to flourishing through grit.

3.4.6. Consistency of Interest -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing

Similarly, the indirect effect of Consistency of Interest on Flourishing via Grit and Spiritual Fortitude was significant (β = 0.005, t = 3.059, p = 0.002), highlighting the role of spiritual fortitude in enhancing the effect of consistency of interest on flourishing.

3.4.7. Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing

Finally, the indirect effect of Grit on Flourishing via Spiritual Fortitude was significant (β = 0.317, t = 13.614, p < 0.001), confirming that spiritual fortitude partially mediates the relationship between grit and flourishing.

These specific indirect effects provide a nuanced understanding of the relationships between the sub-dimensions of grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing. They demonstrate that while both consistency of interest and perseverance of effort contribute to flourishing, perseverance of effort plays a more dominant role, particularly through its influence on spiritual fortitude. The results of total indirect effects can be seen in Table 6 and specific indirect effects can be seen in Table 7.

| - | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency of Interest -> Flourishing | 0,010 | 0,003 | 3,147 | 0,002 |

| Consistency of Interest -> Spiritual Fortitude | 0,010 | 0,003 | 3,155 | 0,002 |

| Grit -> Flourishing | 0,318 | 0,023 | 13,614 | 0,000 |

| Perseverance of Effort -> Flourishing | 0,579 | 0,023 | 25,396 | 0,000 |

| Perseverance of Effort -> Spiritual Fortitude | 0,614 | 0,021 | 29,049 | 0,000 |

3.5. Descriptive Analysis of the Effect of Bullying Experiences

Based on descriptive analysis, it was found that respondents who had never experienced bullying would have more grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing. Meanwhile, respondents who still experienced bullying when they were over 15 years old would feel the experience more and have an effect on lower grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing. Bullying experiences reported by respondents as having been experienced when they were 5 to 10 years old or when they were 11 to 15 years old tended to show lower values than bullying experiences that had occurred when they were over 15 years old. This shows that the timing of the bullying incident experienced by respondents can also have an effect on the subject. When the incident occurred when the subject was still small or several years earlier, the effect of the incident would not be as great as when the incident was only experienced in the nearest time or when they were over 15 years old. The results of the significance value of the difference test of spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing when viewed from the timing of bullying experienced also show significant differences. The complete results of this descriptive analysis can be seen in Table 8.

Another descriptive analysis shows that from the three types of bullying, there are various results from their effect on spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing. When respondents experience all three types of bullying (verbal, physical, and social), the level of spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing of participants will be much lower than respondents who do not experience a combination of the three types of bullying. When viewed separately, social bullying has a lower value on spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing compared to verbal bullying and physical bullying. Meanwhile, when comparing verbal bullying and physical bullying, verbal bullying tends to have a more negative effect on the psychological condition of respondents than physical bullying. In addition, bullying involving a combination of 2 types of bullying shows that bullying with a combination of verbal and social types has a worse effect on the psychological condition of respondents than verbal and physical types or social and physical types. The results of the significance value of the difference test of spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing when viewed from the category of bullying types experienced also show significant differences. The complete results of this descriptive analysis can be seen in Table 9. Although these descriptive analyses were not statistically integrated into the SEM due to the scope and design of the study, they provide contextual insights that help interpret the variation in grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing based on different bullying experiences. These findings offer directions for future research to model timing and types of bullying as potential moderators or covariates.

| - | Sample Mean (M) | Standard Deviation (STDEV) | T statistics (|O/STDEV|) | p-values |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistency of Interest -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude | 0,010 | 0,003 | 3,155 | 0,002 |

| Perseverance of Effort -> Grit -> Flourishing | 0,266 | 0,030 | 8,826 | 0,000 |

| Perseverance of Effort -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing | 0,313 | 0,023 | 13,623 | 0,000 |

| Perseverance of Effort -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude | 0,614 | 0,021 | 29,049 | 0,000 |

| Consistency of Interest -> Grit -> Flourishing | 0,004 | 0,001 | 3,005 | 0,003 |

| Consistency of Interest -> Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing | 0,005 | 0,002 | 3,059 | 0,002 |

| Grit -> Spiritual Fortitude -> Flourishing | 0,318 | 0,023 | 13,614 | 0,000 |

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study confirm the first hypothesis, which posits that grit directly predicts flourishing among adolescent bullying victims. This aligns with prior research indicating that grit promotes long-term goal commitment and perseverance, thereby supporting positive mental health outcomes [21, 31]. Adolescents with higher grit may be better equipped to maintain motivation and overcome emotional setbacks caused by bullying, resulting in enhanced psychological well-being.

The second hypothesis, stating that grit predicts spiritual fortitude, was also supported. This suggests that individuals who are persistent and goal-oriented may also draw upon internal spiritual resources when facing adversity. Previous

| - | N | Mean | Min | Max | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual_Fortitude | Never Experienced |

75 | 42.74 | 32.00 | 45.00 | 0.00 |

| Between Age 5 – 10 | 647 | 36.96 | 9.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Between Age 11 – 15 | 390 | 32.55 | 15.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| More than 15 | 103 | 26.77 | 9.00 | 42.00 | - | |

| Total | 1215 | 35.04 | 9.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Flourishing | Never Experienced | 75 | 40 | 40.00 | 40.00 | 0.00 |

| Between Age 5 – 10 | 647 | 33.21 | 30.00 | 39.00 | - | |

| Between Age 11 – 15 | 390 | 26.77 | 24.00 | 29.00 | - | |

| More than 15 | 103 | 21.02 | 8.00 | 24.00 | - | |

| Total | 1215 | 30.53 | 8.00 | 40.00 | - | |

| Grit | Never Experienced | 75 | 39.79 | 25.00 | 55.00 | 0.00 |

| Between Age 5 – 10 | 647 | 35.34 | 17.00 | 55.00 | - | |

| Between Age 11 – 15 | 390 | 31.82 | 15.00 | 46.00 | - | |

| More than 15 | 103 | 29.11 | 12.00 | 50.00 | - | |

| Total | 1215 | 33.96 | 12.00 | 55.00 | - | |

| - | N | Mean | Min | Max | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spiritual-Fortitude | verbal | 91 | 39.48 | 22.00 | 45.00 | 0.00 |

| Social | 176 | 37.30 | 26.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Physical | 69 | 40.41 | 22.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Verbal+Social | 173 | 30.39 | 13.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Verbal+Physical | 179 | 34.06 | 22.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Social+Physical | 383 | 34.63 | 9.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| All Type Bullying | 69 | 26.22 | 9.00 | 42.00 | - | |

| No bully | 75 | 42.75 | 32.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Total | 1215 | 35.04 | 9.00 | 45.00 | - | |

| Flourishing | verbal | 91 | 35.98 | 35.00 | 37.00 | 0.00 |

| Social | 176 | 33.60 | 32.00 | 35.00 | - | |

| Physical | 69 | 38.16 | 37.00 | 39.00 | - | |

| Verbal+Social | 173 | 24.42 | 23.00 | 26.00 | - | |

| Verbal+Physical | 179 | 29.23 | 26.00 | 31.00 | - | |

| Social+Physical | 383 | 29.85 | 27.00 | 32.00 | - | |

| All Type Bullying | 69 | 20.01 | 8.00 | 23.00 | - | |

| No bully | 75 | 40 | 40.00 | 40.00 | - | |

| Total | 1215 | 30.53 | 8.00 | 40.00 | - | |

| Grit-Total | verbal | 91 | 37.37 | 22.00 | 53.00 | 0.00 |

| Social | 176 | 35.61 | 17.00 | 48.00 | - | |

| Physical | 69 | 37.46 | 29.00 | 55.00 | - | |

| Verbal+Social | 173 | 32.27 | 15.00 | 50.00 | - | |

| Verbal+Physical | 179 | 32.73 | 22.00 | 46.00 | - | |

| Social+Physical | 383 | 33.19 | 19.00 | 46.00 | - | |

| All Type Bullying | 69 | 27.07 | 12.00 | 37.00 | - | |

| No bully | 75 | 39.79 | 25.00 | 55.00 | - | |

| Total | 1215 | 33.96 | 12.00 | 55.00 | - | |

studies have shown that grit is positively associated with meaning-making and existential coping [16], both of which are foundational aspects of spiritual fortitude. Furthermore, spiritual development has been found to flourish when individuals possess psychological traits such as perseverance and long-term focus [28, 31]. This finding highlights the interconnectedness of personal and spiritual strength in resilience-building processes, particularly within cultures where spirituality plays a central role, such as Indonesia [25].

The third hypothesis, which proposed that spiritual fortitude mediates the relationship between grit and flourishing, was also supported. The path analysis results demonstrated a significant indirect effect of grit on flourishing through spiritual fortitude. This aligns with findings from Wong [32], who emphasized that spiritual meaning-making often serves as a mediator between adversity and well-being. Similarly, other research [33] found that spiritual strength could buffer the negative effects of stress while enhancing life satisfaction and flourishing. This supports the idea that grit may enhance flourishing not only through direct pathways but also via the strengthening of spiritual endurance, which helps individuals assign meaning to their suffering and persevere with hope.

The role of grit sub-dimensions also merits further discussion. Although both consistency of interest and perseverance of effort contribute to overall grit, the findings indicate that perseverance plays a significantly stronger role. This aligns with prior research suggesting that sustained effort, rather than mere interest, is more predictive of long-term resilience outcomes [24, 16]. In contexts of adversity such as bullying, the ability to persist through hardship may be more critical than maintaining consistent goals.

Based on the analysis of additional descriptive data, the data shows that the timing of bullying also affects the psychological condition of the respondents. In the results, it was found that respondents who had never experienced bullying tended to have higher spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing values than respondents who had experienced bullying. The timing of bullying that occurred at the age of over 15 years seemed to have the most visible effect compared to other age timings because it had the lowest values in terms of spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing. Research by Sigurdson et al. [7], Ngo et al. [34], and Arseneault [35] consistently shows that bullying—regardless of when it occurs—can lead to internalizing problems, including depression and anxiety, persisting into adulthood. Bullying in higher education, as discussed by Tight [36] and Myers and Cowie [37], tends to result in more severe psychological outcomes due to the social and academic pressures experienced during this life stage. Therefore, when respondents in this study answered that the bullying still occurred over the age of 15 years, then the respondents are likely experiencing the bullying conditions. This then causes respondents who are still experiencing bullying to report lower spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing values.

Based on the analysis of the following descriptive additional data, it was found that among the three types of bullying (verbal, social, and physical), there were similarities in the results, namely, social bullying had a greater effect on the condition of the participant respondents because it had the lowest values for spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing. Furthermore, when verbal and physical are compared, physical bullying tends to have lesser effect than verbal bullying because verbal bullying has lower values for spiritual fortitude, grit, and flourishing on respondents. Torres et al. [38] found that social bullying, due to its chronic and covert nature, often leads to more serious mental health outcomes than physical bullying. Supporting this, Cho and Lee [39] highlighted that a combination of verbal and social bullying compounds harms and increases vulnerability in victims. As a closing conclusion on the descriptive results, it appears that respondents who experience all types of bullying will have the lowest values for spiritual fortitude, grit and flourishing. Table 9 provides important insights into the differential psychological effects of various types of bullying. Notably, the combination of verbal and social bullying is associated with the lowest levels of grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing, emphasizing the compounded harm of multiple bullying types.

Despite these positive findings, some limitations should be considered. The study’s cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal conclusions, and the reliance on self-reported data may introduce biases. Future research could benefit from longitudinal studies to better understand the temporal relationships between grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing. Additionally, while the sample size was robust, the study's use of convenience sampling may limit the generalizability of the findings to other adolescent populations in Indonesia. Further research could explore how these relationships play out across different cultural or religious contexts.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the present study highlights the importance of both grit and spiritual fortitude in promoting flourishing among adolescent victims of bullying in Indonesia. The findings suggest that while grit serves as a foundation for resilience, spiritual fortitude acts as a crucial mediator that enhances adolescents’ ability to recover and thrive after traumatic experiences. These results have practical implications for mental health interventions and educational policies, emphasizing the need for programs that foster both perseverance and spiritual resilience. Future interventions should focus on strengthening these traits to support adolescent victims of bullying in achieving long-term psychological well-being and flourishing.

STUDY LIMITATIONS

Despite its valuable findings, this study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causal relationships between grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing. Future research should consider longitudinal studies to examine the long-term effect of these psychological factors on adolescent well-being. Second, the self-reported data used in this study may introduce social desirability bias, as participants might have responded in a manner they perceived as socially acceptable rather than reflecting their true experiences. Utilizing mixed-method approaches or incorporating objective psychological assessments in future studies could mitigate this limitation. Third, convenience sampling was used, which may limit the generalizability of findings beyond the study’s sample population. Future studies should employ random sampling methods to enhance external validity. Fourth, the sample was predominantly Protestant (56.8%), which may have influenced the findings related to spiritual fortitude. Future research should consider a more religiously diverse sample or examine whether religious affiliation moderates the relationship between spiritual fortitude and flourishing. Furthermore, while this study examined mediation effects using Structural Equation Modeling, the cross-sectional nature of the data limits causal interpretations. Mediation analysis assumes temporal sequencing, yet all variables were measured simultaneously. Therefore, the mediational findings should be interpreted as correlational rather than indicative of causal pathways. Longitudinal or experimental studies are recommended for future research to verify the directional influence between grit, spiritual fortitude, and flourishing. Lastly, cultural and religious diversity among the participants was not extensively examined as a moderating factor, which could be explored in future research to provide a more nuanced understanding of the role of spiritual fortitude in different sociocultural contexts.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: S.Y.R.: Study conception and design; K.R.L.: Conceptualization; R.P.: Data collection; T.L.: Draft manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| SEM | = Structural Equation Modeling |

| AVE | = Average Variance Extracted |

| SRMR | = Standardized Root Mean Square Residual |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

Ethical approval for this study was granted by the ethics committee of universitas pelita harapan, Indonesia (approval No. 143/LPPM-UPH/VII/2024).

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of institutional and/or research committee and with the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

All participants provided informed consent prior to their involvement in the study. For participants under the age of 18, written consent was also obtained from their parents or legal guardians.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data supporting the findings of this article is available in the Zenodo Repository at https://doi.org/ 10.5281/zenodo.15662457, reference number: 10.5281/zenodo.15662457

FUNDING

This research is a fundamental basic research funded by the Indonesian Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology under contract number 819/LL3/AL.04/ 2024 and a research agreement with the University under contract number 023/LPPM-UPH/VI/2024.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The researchers would like to express their gratitude to the Indonesian Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, as well as Universitas Pelita Harapan, for supporting the implementation of this research program.