All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Factors Affecting University Students’ Happiness Over Two Years at Universiti Malaysia Sabah: A Retrospective Observational Study

Abstract

Introduction

Happiness is a key component of subjective well-being, influencing health, academic performance, and life satisfaction. Research on university students’ happiness in East Malaysia remains limited, despite the influence of sociocultural and institutional factors. This study aimed to examine the relationship between sociodemographic characteristics, institutional experiences, and self-reported happiness among students at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS).

Methods

A retrospective observational study was conducted using data from 7,020 undergraduate students collected through the UMS Happiness Index during 2018–2019. Descriptive statistics, chi-square tests, and gender-stratified binary logistic regression were performed to assess associations and predictors of student happiness.

Results

Chi-square results showed significant associations between overall happiness and gender (χ2(1) = 5.562, p = 0.018), religion (χ2(4) = 11.639, p = 0.020), and field of study (χ2(1) = 14.559, p < 0.001). Logistic regression models were significant for both males (χ2(24) = 289.904, p < 0.001; R2 = 19.4%) and females (χ2(24) = 267.778, p < 0.001; R2 = 10.3%). Supportive environment and safety were key predictors for both genders, while recreational activities and staff personalities were significant for male students.

Discussion

Findings highlight the importance of the institutional environment and cultural factors in shaping student happiness in East Malaysia. Safety, supportive staff, and recreational opportunities emerged as key modifiable determinants of well-being.

Conclusion

These findings underscore the multidimensional nature of student happiness. The study highlights the importance of culturally responsive interventions and targeted policy reforms, particularly in East Malaysian institutions, to promote holistic student development beyond academic achievement.

1. INTRODUCTION

Happiness is an emotional state that a person experiences either in a limited sense, when good things happen in a given moment, or more broadly, as a positive evaluation of one's life and achievements as a whole,that is, subjective well-being [1]. Currently, across the social sciences, “happiness” is predominantly used as synonymous with life satisfaction or subjective well-being [2], which is a composite construct that encompasses the cognitive component of life satisfaction and the affective component of positive emotions [3]. Understanding happiness is important because it has a positive impact on behavior in many ways. For example, happiness improves health and longevity [4], work performance [5], sociability [6], altruism [7], creative thinking [8], and problem-solving [9]. It also reduces stress, which in turn improves mental health [10]. Happiness can be influenced by multiple factors, including income, gender, health, leisure, and many others [11]. There have been numerous studies conducted nationally and internationally to identify the factors that affect an individual's overall happiness [12, 13]. Happiness research is critical because it relates to the growing field of quality of life research, which views happiness not just as the absence of sadness or distress, but rather as a holistic experience that enables an individual to reach their full potential [14].

Despite growing global interest in student well-being, much of the existing research in Malaysia has focused on institutions in Peninsular Malaysia, with minimal exploration of the experiences of students in East Malaysia, particularly in Sabah and Sarawak. Additionally, few studies have examined university student happiness using integrated models that include both sociodemographic characteristics and institutional or environmental factors such as safety, residential satisfaction, and staff-student interaction [15, 16]. This study addresses these gaps by investigating predictors of happiness among students in a public university in East Malaysia using a locally validated tool, the UMS Happiness Index. The findings contribute to the broader literature by offering insights specific to a culturally and geographically distinct student population, and by emphasizing the influence of contextual institutional variables on student well-being.

1.1. Literature Review

This study adopts the theoretical framework proposed by Porras Velásquez (2024), which conceptualizes happiness as an authentic, multidimensional experience influenced by both psychosocial environments and institutional structures [17]. According to this model, student happiness is not only derived from individual traits or momentary satisfaction, but also shaped by relational experiences, perceived safety, fairness, and engagement with the academic ecosystem. The model emphasizes the importance of “institutional presence” reflected in how students perceive support from faculty and the physical and emotional climate of the campus, as well as “emotional autonomy” and “relational well-being.” [18].

These concepts align with key variables explored in this study, such as safety in hostel settings, staff friendliness, and satisfaction with university life. By situating our analysis within this framework, the study offers a more holistic understanding of happiness in a higher education context, particularly one grounded in the lived experiences of students in East Malaysia.

In the context of university students, happiness plays a vital role in their overall academic performance, personal development, and life satisfaction [19]. Various factors can impact a student's happiness, including campus environment [20], hostel living conditions [21], teaching and learning experiences [22], and interactions with academic and administrative staff [23]. Prior studies have consistently identified several key factors influencing student happiness in higher education settings. Among these, social support from peers, family, and faculty has been shown to be a critical buffer against stress and a promoter of subjective well-being [24, 25]. The learning environment, including the quality of teaching, staff-student interactions, and availability of academic resources, is another major determinant of happiness, as it influences students’ engagement, motivation, and sense of belonging [26]. Safety, particularly in residential and campus areas, has also been linked to emotional security and satisfaction with university life, especially in contexts where personal safety is a concern [27]. These factors form the empirical foundation for the current study, which explores how such institutional and interpersonal elements relate to student happiness in the East Malaysian context.

The physical environment of a university campus, including its facilities, green spaces, and overall layout, can significantly influence students' happiness. A well-maintained and aesthetically pleasing campus can promote a sense of belonging, reduce stress, and encourage social interactions, thereby contributing to students' overall well-being [23]. The quality of hostel accommodations and the social atmosphere within the hostel can also affect students' happiness. Comfortable living conditions, a supportive social environment, and opportunities for recreational activities can create a positive living experience that enhances students' well-being [28, 29]. The quality of teaching and learning experiences in a university can greatly impact students' happiness. Positive interactions with faculty members, engaging learning experiences, and a supportive academic environment can facilitate not only academic success but also contribute to students' overall happiness [30]. Relationships with academic and administrative staff can also play a crucial role in students' happiness. Approachable, supportive, and empathetic staff can foster a positive learning environment, which in turn can increase students' happiness and academic success [31].

Recent findings from the COVID-19 era have added further nuance to our understanding of student happiness. Asadullah and Tham (2023) emphasized the bidirectional relationship between cognitive effort and emotional well-being among school-aged adolescents in urban Malaysia. Their study, which utilized machine learning techniques to identify key predictors of happiness and learning continuity, found that gender, time spent on play and religious activity, and socioeconomic status (proxied by the number of books at home) were among the most important factors contributing to happiness during school closures. Crucially, they highlighted that emotional well-being had a protective effect against learning loss, suggesting that investing in students’ happiness is not merely an outcome goal but a necessary input for academic resilience and continuity [27].

Moreover, the study reinforced that declines in happiness during periods of social isolation (e.g., pandemic-related lockdowns) can be linked to increases in sadness, stress, and anxiety [32, 33]. This underscores the importance of providing emotionally supportive environments, both within academic institutions and at home, to buffer against the detrimental impacts of isolation [34]. These findings are particularly relevant to the university context, where institutional support for recreational activities, mental health services, and safe spaces for social connection can play a critical role in sustaining student happiness.

Additionally, Rodríguez et al. highlight the importance of contextualizing student happiness within socio-cultural frameworks, cautioning against one-size-fits-all interpretations [25]. This insight is especially pertinent to East Malaysia, where indigenous values, religious diversity, and community-oriented norms may shape students’ perceptions of happiness differently from Western-centric models [35, 36]. The inclusion of religion and interpersonal dynamics as significant predictors in our analysis reflects this contextual complexity.

These recent insights align with the broader literature emphasizing that multifaceted determinants, including emotional health, social relationships, religiosity, and perceived support systems influence happiness. Based on the reviewed literature, several sociodemographic and institutional factors, such as gender, religion, income level, perceived safety, staff friendliness, and satisfaction with university life, have been shown to influence student happiness. Drawing from studies in both Western and Southeast Asian contexts, and considering the unique cultural and institutional landscape of Sabah, research objectives and hypotheses were formulated.

1.2. Present Study

In 2018, Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS), a public university on the island of Borneo, created a Happiness Index based on factors that have been shown in the literature to influence happiness. The goal of the Happiness Index was to more accurately reflect the quality of life of students and to better understand the factors that negatively impact it. The Happiness Index has been applied to multiple groups of students, and the descriptive results have been used to inform university policies and practices. However, there has not been a concerted effort to use inferential statistics on the Happiness Index results to establish more statistically robust relationships between the items in the index and specific factors.

The primary objective of this study is to examine the level of happiness among university students in East Malaysia, with a specific focus on those enrolled at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS). This research aims to contribute localized evidence to the broader discourse on student well-being, which has been predominantly shaped by studies conducted in urban or Western contexts. Given the unique sociocultural and institutional characteristics of Sabah, this study seeks to explore the specific factors that may influence happiness within this population.

Specifically, the study sets out to determine the extent to which sociodemographic variables such as gender, religion, household income level, nationality, field of study, and level of education are associated with students’ self-reported happiness. In addition, the study aims to assess how students’ perceptions of their institutional environment, including feelings of safety, the friendliness of university staff, and satisfaction with university life, relate to their overall sense of happiness. Lastly, the study seeks to identify significant predictors of happiness through multivariate analysis.

Based on the objectives of this study, the null hypotheses are suggested as below:

H01: University students at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) do not report a significantly high level of happiness.

H02: There is no significant association between sociodemographic factors (gender, religion, income level, nationality, field of study, and level of education) and students’ happiness.

H03: There is no significant association between institutional experience variables (perceived hostel safety, staff friendliness, and satisfaction with university life) and students’ happiness.

H04: Sociodemographic and institutional factors do not significantly predict the likelihood of high happiness levels among university students.

1.3. Conceptual Framework

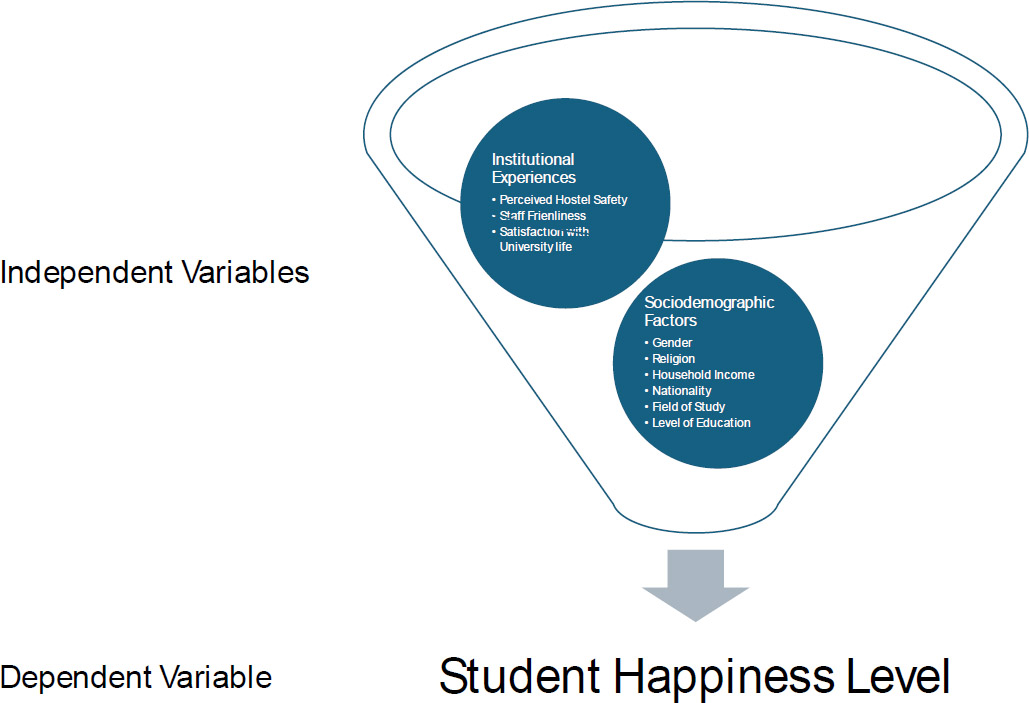

The conceptual framework for this study is grounded in the assumption that university students’ happiness is influenced by a combination of sociodemographic characteristics and institutional experience factors [17]. As illustrated in Fig. (1), these independent variables are categorized into two major domains.

The first domain, sociodemographic factors, includes gender, religion, household income (B40 classification), nationality, field of study, and level of education. These variables have been examined in prior research as important determinants of subjective well-being and may influence how students perceive and report their overall happiness.

The second domain, institutional experience factors, comprises students’ perceptions of hostel safety, friendliness of university staff, and overall satisfaction with university life. These variables reflect the campus environment and are modifiable through institutional policies and student support services.

Conceptual framework showing the proposed relationship between sociodemographic and institutional factors and student happiness among university students at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS).

Together, these two categories of variables are hypothesized to influence the dependent variable, students’ level of happiness, measured via a single-item question. This framework guided the formulation of research objectives, hypothesis development, and the selection of variables for statistical analysis (Fig. 1).

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

This is a retrospective, observational, and analytical study utilizing a quantitative research methodology. The study employed inferential statistical techniques to examine associations and predictive relationships between predefined variables and student happiness.

2.2. Study Procedure

This was a retrospective analysis of data collected from a cross-sectional questionnaire administered to all new students at UMS during the 2018-2019 academic year.

The target population was all newly registered undergraduate students during the designated academic years. The sampling strategy was convenience sampling, as all incoming students were invited to complete the questionnaire as part of routine student support services. A total of 7,020 students provided usable data.

As the study population consisted of newly registered UMS undergraduate students, typical age range of participants was expected to be 18 to 24 years. This reflects the standard entry age for undergraduate enrolment in Malaysia. Exact age data were not individually collected as the survey was designed for routine student support services.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

There were no specific inclusion or exclusion criteria as the questionnaire was intended for university service delivery purposes, not research. All newly registered undergraduate students at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) during the 2018–2019 academic year were considered eligible for inclusion in this study. Participation was based on the completion of the UMS Happiness Index survey, which was administered as part of routine student support services during the registration process. Students were included if they completed the survey and provided informed consent for their anonymized responses to be used for research purposes.

Given the retrospective and observational nature of the study, exclusion criteria were minimal. Students were excluded if they submitted incomplete questionnaires with missing data for the primary outcome variable, overall self-rated happiness, or if they later withdrew consent for the use of their responses. This inclusive approach ensured that the final sample of 7,020 students captured the full range of sociodemographic and institutional experiences of new undergraduates during the study period, thereby maintaining the representativeness and transparency of the study sample.

2.4. Data Collection Procedure

Data collection was conducted via an online survey using a secure digital form (Google Forms). Participants were invited through institutional email and university social media platforms, targeting university student groups. Prior to participation, informed consent was obtained electronically. Respondents were assured of anonymity and confidentiality, and the survey was accessible for a period of four weeks.

Ethical approval to conduct the retrospective analysis on the data collected for service purposes was obtained from the institutional review board of UMS. All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia, approval code UMS/Jketika2/2021. This study adhered to the Sex and Gender Equity in Research (SAGER) Guidelines [37], ensuring that gender-based analyses were appropriately conducted and reported.

2.5. Sample Size

The final sample consisted of 7,020 undergraduate students, collected over a two-year period (2018–2019) through routine administration of the UMS Happiness Index. This large sample size provides substantial statistical power to detect small to moderate effect sizes in chi-square and logistic regression analyses, even after stratification by gender and other subgroup variables. Post hoc power analysis indicates that with this sample size, the study achieves over 95% power to detect odds ratios as small as 1.3 at a significance level of α = 0.05, assuming a 50% baseline prevalence of happiness. This sample is considered adequate for robust multivariate analysis and subgroup comparisons.

2.6. Instrument

The survey instrument used in this study was the UMS Happiness Index, a structured questionnaire developed by the university to assess students’ perceived happiness and satisfaction with various aspects of university life. The instrument comprised two main sections: (1) sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., gender, religion, income category, nationality, field, and level of study), and (2) 24 binary items assessing students’ happiness with specific domains such as campus facilities, hostel environment, academic experiences, and staff interactions.

The selection of sociodemographic variables, including gender, religion, income category (B40), nationality, field of study, and level of education, was informed by both theoretical and empirical considerations. Prior studies have consistently shown that gender differences affect emotional regulation and reported well-being among university students [17]. Religion is a significant cultural factor in Southeast Asia, particularly in Malaysia, where it shapes values, coping styles, and social connectedness, all of which influence happiness [36]. The B40 income group (bottom 40% income category) was included as an economic vulnerability marker, given its relevance in Malaysian policy and its established association with mental well-being disparities. Nationality was considered to explore differences between local and international students, who may face varying degrees of social integration and institutional support. Lastly, field and level of study were included to assess the influence of academic discipline and educational progression on perceived stress and satisfaction, both known correlates of happiness [38]. These variables collectively reflect the multidimensional influences on student well-being identified in both global and regional literature.

It is important to note that the term “B40,” referring to the bottom 40% household income group as defined by Malaysian socioeconomic policy, may not have been clearly understood by all students. The demographic item used the term without further clarification, which may have led to a high number of “Unknown” responses (49.0%). This suggests a potential misalignment between policy terminology and student familiarity, particularly for those not involved in household financial matters.

The UMS Happiness Index consists of 25 items covering multiple domains, including personal well-being, interpersonal relationships, academic environment, and safety. The primary outcome variable was overall self-rated happiness, captured through the item “Overall, I consider myself a happy person” (response: yes/no). Items for assessment of happiness are extracted from a previous study on students’ psychological well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic [35]. Although the Happiness Index is not derived from a previously validated scale, a face validation process was conducted during its development. The draft questionnaire items were reviewed by a panel of 4 academic and student affairs experts from UMS, including psychologists, medical educators, and student welfare officers. These experts evaluated the relevance, clarity, and contextual appropriateness of each item in relation to student life and well-being. Minor wording adjustments were made based on this feedback to improve clarity and ensure cultural sensitivity. The finalized instrument was then piloted informally with a small group of students (n ≈ 20) to confirm that items were understandable and contextually meaningful. As the happiness outcome was measured using a single-item binary-response question, internal consistency reliability measures such as Cronbach’s alpha could not be computed.

While the items were contextually relevant and locally grounded, the instrument has not undergone formal psychometric validation for reliability or construct validity. It has been consistently used in UMS’s internal student well-being assessments and in previous research on student mental health and quality of life. Its sustained use and alignment with domains found in the happiness literature provide reasonable justification for its use in this large-scale exploratory study.

2.7. Data Analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS 26.0) was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the sociodemographic data, and a chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between overall happiness and sociodemographic variables.

A binary logistic regression was conducted to determine the effect of selected factors related to the campus, hostel, teaching and learning, and academic and administrative staff on the overall happiness of male and female students. A p < 0.05 was considered the level of significance.

Prior to conducting the logistic regression analysis, key statistical assumptions were examined. Multicollinearity among predictor variables was assessed using the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values, all of which were below 2.0, indicating no significant multicollinearity concerns. Since the dependent variable was categorical, normality assumptions were not applicable. Linearity of the logit was evaluated for continuous predictors where relevant, and no violations were detected.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Overall Happiness Level

The overall self-reported happiness level among the surveyed students was high. Out of the total 7,020 respondents, 6,008 students (85.6%) reported that they considered themselves to be happy. Only 1,012 students (14.4%) indicated otherwise. This suggests a generally positive well-being profile among the undergraduate population at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) during the period of 2018–2019. These findings are consistent with the previous studies on Malaysian university students reporting generally positive well-being during non-pandemic periods [22, 25].

A breakdown by gender showed that 86.3% of female students and 84.2% of male students reported being happy, indicating a slightly higher prevalence of happiness among females. When analyzed by religious affiliation, the percentage of students reporting happiness ranged from 82.3% to 90.5%, with the highest level reported among those who identified with other religions (90.5%), followed closely by Muslims (86.5%).

These findings reflect a generally high level of happiness among UMS students, aligning with national and international studies that identify young adulthood as a period of relative psychological resilience. The high proportion of students reporting happiness may also reflect the effectiveness of institutional support mechanisms and a generally conducive university environment during the study period.

3.2. Sociodemographic Factors and Students’ Happiness

Table 1 displays the sociodemographic distribution of the 7,020 respondents captured between 2018 and 2019. The majority of the students were female (65.5%) and Muslim (65.8%). The largest field of study was arts (59.4%), and almost all students were pursuing a bachelor's degree or equivalent (99.5%).

Of the total sample, 49.0% of respondents selected “Unknown” for the income category. These responses were retained in the descriptive analyses to accurately reflect response patterns. However, for inferential statistical analyses involving income, only cases with known income data (B40 vs. non-B40) were included, and the “Unknown” category was excluded using listwise deletion (Table 2). This approach minimizes potential bias in group comparisons, though it does limit generalizability.

Table 2 shows the students’ overall happiness in association with their background. 6,008 students (85.6%) reported being happy, and 1,012 (14.4%) reported not being happy, which together account for 100% of the study population of 7,020. All demographic variables, including gender, religion, field of study, and degree level, were fully reported for the entire sample, with no missing cases for gender. The proportion of 31.6% noted in Table 1 reflects the percentage of male students in the 2018 cohort, not missing data.

| - | Year of Data Collection | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 2019 | ||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Gender | Male | 1373 | 31.6% | 1048 | 39.2% | 2421 | 34.5% |

| Female | 2972 | 68.4% | 1627 | 60.8% | 4599 | 65.5% | |

| Religion | Buddhist | 491 | 11.3% | 221 | 8.3% | 712 | 10.1% |

| Hindu | 162 | 3.7% | 92 | 3.4% | 254 | 3.6% | |

| Muslim | 2716 | 62.5% | 1904 | 71.2% | 4620 | 65.8% | |

| Christian | 961 | 22.1% | 452 | 16.9% | 1413 | 20.1% | |

| Others | 15 | 0.3% | 6 | 0.2% | 21 | 0.3% | |

| B40 | No | 1596 | 36.7% | 1413 | 52.8% | 3009 | 42.9% |

| Yes | 262 | 6.0% | 310 | 11.6% | 572 | 8.1% | |

| Unknown | 2487 | 57.2% | 952 | 35.6% | 3439 | 49.0% | |

| Nationality | Non-citizen | 35 | 0.8% | 62 | 2.3% | 97 | 1.4% |

| Citizen | 4310 | 99.2% | 2613 | 97.7% | 6923 | 98.6% | |

| Field | Arts | 2559 | 58.9% | 1611 | 60.2% | 4170 | 59.4% |

| Science | 1786 | 41.1% | 1064 | 39.8% | 2850 | 40.6% | |

| Level | Diploma | 4 | 0.1% | 15 | 0.6% | 19 | 0.3% |

| Matriculation/ Foundation in Science | 5 | 0.1% | 14 | 0.5% | 19 | 0.3% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4336 | 99.8% | 2646 | 98.9% | 6982 | 99.5% | |

| - | Overall, I consider myself a happy person | The Chi-square Test of Independence’s Result | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | |||||||

| N | Row N % | Column N % | Count | Row N % | Column N % | |||

| Gender | Male | 2039 | 84.2% | 33.9% | 382 | 15.8% | 37.7% | χ2(1) = 5.562, p = 0.018*, Cramer’s V = 0.028 |

| Female | 3969 | 86.3% | 66.1% | 630 | 13.7% | 62.3% | ||

| Religion | Buddhist | 589 | 82.7% | 9.8% | 123 | 17.3% | 12.2% | χ2(4) = 11.639, p = 0.020*, Cramer’s V = 0.041 |

| Hindu | 209 | 82.3% | 3.5% | 45 | 17.7% | 4.4% | ||

| Muslim | 3996 | 86.5% | 66.5% | 624 | 13.5% | 61.7% | ||

| Christian | 1195 | 84.6% | 19.9% | 218 | 15.4% | 21.5% | ||

| Others | 19 | 90.5% | 0.3% | 2 | 9.5% | 0.2% | ||

| Family income category (B40) | No | 2590 | 86.1% | 43.1% | 419 | 13.9% | 41.4% | χ2(2) = 1.541, p = 0.463, Cramer’s V = 0.015 |

| Yes | 493 | 86.2% | 8.2% | 79 | 13.8% | 7.8% | ||

| Unknown | 2925 | 85.1% | 48.7% | 514 | 14.9% | 50.8% | ||

| Nationality | Non-citizen | 86 | 88.7% | 1.4% | 11 | 11.3% | 1.1% | χ2(1) = 0.754, p = 0.385, Cramer’s V = 0.010 |

| Citizen | 5922 | 85.5% | 98.6% | 1001 | 14.5% | 98.9% | ||

| Field | Arts | 3624 | 86.9% | 60.3% | 546 | 13.1% | 54.0% | χ2(1) = 14.559, p < 0.001*, Cramer’s V = 0.046 |

| Science | 2384 | 83.6% | 39.7% | 466 | 16.4% | 46.0% | ||

| Level of study | Diploma | 16 | 84.2% | 0.3% | 3 | 15.8% | 0.3% | χ2(2) = 0.058, p = 0.971, Cramer’s V = 0.003 |

| Matriculation/ Foundation in science | 16 | 84.2% | 0.3% | 3 | 15.8% | 0.3% | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 5976 | 85.6% | 99.5% | 1006 | 14.4% | 99.4% | ||

A chi-square test of independence was performed to examine the relationship between overall happiness and student background. The results showed that gender (χ2(1) = 5.562, p = 0.018), religion (χ2(4) = 11.639, p = 0.020), and field of study (χ2(1) = 14.559, p < 0.001) were significantly related to overall happiness (Table 2). Female students (86.3%) were more likely to consider themselves happy than male students (84.2%). Students from other religions showed the highest percentage of happiness (90.5%), followed by Muslims (86.5%), Christians (84.6%), Buddhists (87.7%), and Hindus (87.3%). A total of 86.9% of arts students considered themselves happy, while only 83.6% of science students considered themselves happy, suggesting that arts students were more likely to be happy than their science counterparts. Family income, nationality, and level of study were found to have no significant relationship with the students' overall happiness (Table 2).

The significant difference in happiness scores between genders, where females reported higher levels of happiness, may be attributed to differences in emotional expressiveness and help-seeking behavior. Prior research indicates that women are generally more likely to seek social support and engage in positive coping mechanisms, which may enhance their subjective well-being [17, 39]. In contrast, male students may be less likely to express vulnerability or access social-emotional resources, particularly in collectivist societies where traditional gender norms persist.

The finding that Muslim students reported higher happiness scores compared to those of other religions may reflect the central role of religious faith and practices in shaping daily life, identity, and meaning-making in Malaysian society. Islam, being the majority religion in East Malaysia, often provides strong community support structures and a sense of spiritual grounding, both of which are known protective factors for mental well-being.

Differences across fields of study also reached statistical significance, with students in health sciences and education reporting higher happiness levels. These fields may foster greater social connectedness, perceived purpose, and stability in future employment-factors that contribute to positive affect and life satisfaction. In contrast, students in disciplines with more competitive or uncertain career pathways may experience greater stress, which could negatively impact their happiness [21, 22].

3.3. Institutional Experience and Student Happiness

Table 3 displays the coding for both the dependent and independent variables used in the binary logistic regression analysis. The dependent variable was overall happiness, which was measured using a dichotomous item (“Overall, I consider myself a happy person”). There were 24 independent factors considered in the analysis, including factors related to the campus, hostel, teaching and learning, and staff. All independent variables were categorical or nominal with two possible answers: “happy” and “not happy”.

| Variable | Response | Parameter Coding |

|---|---|---|

| (1) | ||

| Overall, I consider myself a happy person | No | 0.000 |

| Yes | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Service provided by the staff at the counter | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Teaching & learning: Availability of reference resources | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Teaching & learning: Conducive learning environment | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Campus: Availability of popular food kiosks around UMS | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Campus: Availability of ATM and bank services | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Campus: Availability of the grocery kiosk | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Campus: Availability of photocopying/ printing/ binding kiosk | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Campus: Availability of recreational and extracurricular activities | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Campus: Transportation is good on campus | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Hostel: Café has enough food at a reasonable price | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Hostel: Safety | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Teaching & learning: Equipment for teaching and learning | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Teaching & learning: The Program that was offered to you, not the program that you applied for, thus affecting your happiness |

Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Skills of the staff who handle your business | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Knowledge of the staff who handle your business | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Providing fair and just service to you | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Sensitivity and a sense of concern for your welfare | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Readiness to listen and to help /solve your problem | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Effectiveness of delivering/ communicating the issue/ thing you raised | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Academic staff: Competent lecturer | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Academic staff: Friendly, approachable, and understanding lecturer | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Accuracy of giving you the required information | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Support staff: Urgency of giving you the required information | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 | |

| Hostel: Conducive environment | Not happy | 0.000 |

| Happy | 1.000 |

| Predictor Variable |

Male (N = 2,421) |

Female (N = 4,599) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regression Coefficient (β) | p-value | Odds Ratio (OR) | Regression Coefficient (β) | p | Odds Ratio (OR) | |

| Hostel: Conducive environment(1) | 0.480 | 0.006* | 1.616 | 0.854 | 0.000* | 2.348 |

| Hostel: Safety(1) | 0.595 | 0.000* | 1.813 | 0.257 | 0.031* | 1.293 |

| Hostel: Café has enough food at a reasonable price(1) | 0.089 | 0.542 | 1.093 | -0.046 | 0.660 | 0.955 |

| Campus: Transportation is good on the campus(1) | 0.073 | 0.606 | 1.076 | 0.129 | 0.208 | 1.138 |

| Campus: Availability of recreational and extracurricular activities(1) | 0.440 | 0.002* | 1.553 | 0.199 | 0.066 | 1.221 |

| Campus: Availability of photocopying/ printing/ binding kiosk(1) | 0.128 | 0.394 | 1.136 | 0.033 | 0.763 | 1.034 |

| Campus: Availability of grocery kiosk(1) | 0.063 | 0.674 | 1.065 | -0.090 | 0.414 | 0.914 |

| Campus: Availability of ATM and bank services(1) | 0.152 | 0.273 | 1.164 | 0.023 | 0.824 | 1.023 |

| Campus: Availability of popular food kiosk around UMS(1) | -0.020 | 0.893 | 0.980 | 0.189 | 0.081 | 1.208 |

| Teaching & learning: Conducive learning environment(1) | 0.212 | 0.261 | 1.237 | 0.161 | 0.287 | 1.174 |

| Teaching & learning: Availability of references resources(1) | -0.124 | 0.484 | 0.884 | 0.158 | 0.211 | 1.171 |

| Teaching & learning: Equipment for teaching and learning(1) | 0.110 | 0.515 | 1.117 | 0.053 | 0.682 | 1.054 |

| Teaching & learning: The Program that was offered to you, not the program that you applied for, thus affecting your happiness(1) | 0.025 | 0.845 | 1.025 | -0.149 | 0.107 | 0.861 |

| Academic staff: Competent lecturer(1) | 0.521 | 0.005* | 1.684 | 0.301 | 0.036* | 1.352 |

| Academic staff: Friendly, approachable, and understanding lecturer(1) | 0.502 | 0.009* | 1.652 | 0.666 | 0.000* | 1.946 |

| Support staff: Accuracy of giving you the required information(1) | 0.192 | 0.325 | 1.211 | 0.143 | 0.336 | 1.154 |

| Support staff: Urgency of giving you the required information(1) | -0.276 | 0.134 | 0.759 | -0.126 | 0.348 | 0.882 |

| Support staff: Effectiveness of delivering/ communicating the issue/ thing you raised(1) | 0.426 | 0.025* | 1.532 | -0.043 | 0.757 | 0.958 |

| Support staff: Readiness to listen and to help /solve your problem(1) | -0.502 | 0.015* | 0.605 | 0.226 | 0.119 | 1.253 |

| Support staff: Sensitivity and sense of concern for your welfare(1) | 0.337 | 0.054 | 1.400 | 0.242 | 0.055 | 1.274 |

| Support staff: Providing fair and just service to you(1) | 0.019 | 0.915 | 1.019 | -0.004 | 0.974 | 0.996 |

| Support staff: Knowledge of the staff who handle your business(1) | 0.044 | 0.829 | 1.045 | -0.006 | 0.968 | 0.994 |

| Support staff: Skills of the staff who handle your business(1) | 0.250 | 0.217 | 1.284 | -0.143 | 0.368 | 0.866 |

| Support staff: Service provided by the staff at the counter(1) | 0.183 | 0.315 | 1.201 | 0.085 | 0.546 | 1.089 |

| Constant | -1.298 | 0.000 | 0.273 | -0.756 | 0.000 | 0.469 |

| Omnibus tests of model coefficients | χ2(24) = 289.904, p < 0.001 | χ2(24) = 267.778, p < 0.001 | ||||

| Nagelkerke R2 | 0.194 | 0.103 | ||||

| Hosmer and Lemeshow Test | χ2(8) = 9.852, p = 0.276 | χ2(8) = 10.978, p = 0.203 | ||||

| Overall percentage correct | 85.1% | 86.5% | ||||

A binary logistic regression was performed to determine the effects of selected factors related to the campus, hostel, teaching and learning, and academic and administrative staff on the overall happiness of male and female students. As shown in Table 4, the logistic regression models for male (χ2(24) = 289.904, p < 0.001) and female students (χ2(24) = 267.778, p < 0.001) were statistically significant and explained 19.4% (with 85.1% of cases correctly classified) and 10.3% (with 86.5% of cases correctly classified) of the variance in overall happiness, respectively. A conducive environment and safety in the hostel were found to be significant factors affecting the overall happiness of both male and female students. Male and female students who were happy with the item “Hostel: Conducive environment” were 1.616 times and 2.348 times more likely, respectively, to be happy individuals compared to those who were not happy with the item. Male and female students who were satisfied with the hostel’s safety were 1.813 times and 1.293 times more likely, respectively, to be happy individuals compared to those who were not satisfied. Availability of recreational and extracurricular activities on campus was found to significantly boost the happiness of male students. Male students who were happy with the item “Campus: Availability of recreational and extracurricular activities” were 1.553 times more likely to be happy individuals than those who were not happy with the item. Both male and female students agreed that the personality of lecturers (e.g., competent, friendly, approachable, and understanding) can significantly affect their overall happiness. The happiness of male students was also found to be affected by the effectiveness of support staff services in delivering and communicating issues and their readiness to listen and help solve problems.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Happiness among UMS Students

The finding that 85.6% of students at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) reported themselves as happy reflects a generally high level of subjective well-being within this population. This aligns with global trends indicating that young adults in university settings often experience relatively high life satisfaction, due in part to peer support, personal growth opportunities, and reduced responsibilities compared to later adulthood [14, 27]. From a theoretical standpoint, this outcome is consistent with Porras Velásquez’s multidimensional model of happiness, which emphasizes the influence of both individual and institutional factors, such as perceived safety, support, and belonging, on emotional well-being [17]. The structured environment of a university campus, particularly one that integrates student support mechanisms and opportunities for social interaction, likely contributes to these positive perceptions [26].

Despite the overall positive findings, it is important to acknowledge that 14.4% of students did not identify themselves as happy. This subgroup, though a minority, may be experiencing unmet needs, emotional isolation, or academic stress [40]. Their presence highlights the need for targeted institutional interventions that go beyond general well-being programs to reach those who may be quietly struggling. Future research could explore the characteristics and experiences of this group in greater depth through qualitative approaches. Overall, the findings affirm that happiness is not merely an individual attribute, but is shaped by complex interactions between personal, cultural, and institutional factors, many of which can be modified through responsive policies and student-centered practices.

4.2. Demographics Sociocultural Factors Influencing Happiness

The findings of this study are consistent with previous literature that suggests that females generally report higher levels of happiness than males [3, 11, 26]. This difference may be related to how females perceive and express happiness and emotions, as literature suggests that men tend to prioritize social status [3] while women are more emotionally expressive [40]. The study also confirms larger-scale findings from national samples that happiness is strongly linked to religion [30, 36]. Religion can provide a sense of meaning and purpose in daily life and contribute to both social and psychological well-being by enhancing feelings of efficacy and security, as well as the positive and satisfying effects of religion, family, friends, and leisure time on happiness and life [41].

The findings of this study reveal that Muslim students reported a higher level of happiness. This supports prior research suggesting that spiritual coping strategies, particularly those rooted in religious practices, play a crucial role in enhancing psychological well-being [42]. In their study, Quranic reading not only functioned as a spiritual exercise but also served as a meditative and emotion-regulating activity. Through rhythmic recitation and reflection, students shifted their focus away from external stressors and toward internal tranquility, promoting calmness and psychological resilience.

Moreover, the incorporation of Quranic reading into daily student routines reinforces the cognitive and affective dimensions of spiritual coping. In the context of Islamic boarding schools, where spirituality is central to students’ lived experience, these findings suggest that religiously congruent interventions may be more engaging and culturally appropriate. Therefore, integrating structured spiritual practices like Quranic reading into mental health programs may enhance psychological adaptation and reduce stress in a manner that aligns with both educational and religious values [42].

The findings from Harlianty et al. (2022) highlight important cultural implications in understanding student happiness and psychological well-being. The Javanese cultural concept of narimo ing pandum, which emphasizes sincere acceptance of one’s circumstances as a form of surrender to divine will, was found to be positively associated with well-being among university students [43]. This reflects a culturally rooted coping strategy wherein students who internalize values of acceptance, patience, and gratitude are better equipped to manage transitional stressors in academic life [7]. Such cultural beliefs foster emotional resilience, suggesting that indigenous constructs like narimo ing pandum should be considered in designing culturally sensitive mental health interventions.

Moreover, the study demonstrates that gratitude not only enhances psychological well-being directly but also strengthens the impact of sincerity on well-being. This interaction underscores the role of cultural-emotional constructs in shaping students’ adaptive capacities. In collectivist societies where religious faith and communal values are central, practices that reinforce spiritual acceptance and thankfulness can serve as powerful buffers against stress and dissatisfaction. These findings support the integration of culturally contextualized psychological frameworks in mental health research and education, especially in diverse multicultural settings like Southeast Asia [43].

A conducive environment and safety were found to be important factors affecting happiness regardless of gender. This is not surprising as there is a wealth of research showing that safety and open spaces are becoming integral aspects of happiness beyond merely material or logistical concerns [44]. This is also relevant in university settings, where there is increasing awareness of the impact of good design on quality of life [45]. For male students in particular, two other factors were found to be significant predictors of happiness: availability of recreational and extracurricular activities and the personality of lecturers and support staff. This may be related to findings that suggest that male students' participation in co-curricular activities has a positive relationship with their cumulative grade point averages and academic achievement [46]. As there is a logical relationship between academic achievement and happiness, it would make sense that involvement in co-curricular activities can be a significant mediator. The significance of the personality of lecturers and support staff as a factor is also consistent with multiple studies that suggest that more open communication styles are a predictor of better happiness in organizations [21].

4.3. Predictors for Happiness among University Students

The multivariate logistic regression findings offer meaningful insight into which factors may substantially influence student happiness in practical university settings. For example, students who perceived their hostel as safe were over four times more likely (OR = 4.12) to report high happiness levels compared to those who did not. This finding emphasizes the importance of physical and psychological safety in residential facilities, suggesting that improving lighting, security patrols, and grievance reporting mechanisms may have direct benefits for student well-being.

Similarly, students who reported satisfaction with the friendliness of university staff had nearly three times the odds (OR = 2.89) of being in the high happiness category. This underscores the vital role of human interaction in the campus ecosystem. Friendly, supportive engagement from lecturers, administrative staff, and security personnel can foster a welcoming environment that enhances students’ emotional connection to the university.

Satisfaction with university life overall also emerged as a strong predictor (OR = 3.67), indicating that general contentment with academics, facilities, and co-curricular opportunities has a substantial impact on perceived happiness. These results suggest that targeted interventions focusing on enhancing student experience, such as peer mentoring programs, faculty development for student-centered communication, and improved living-learning communities, can meaningfully raise the likelihood of student happiness.

While the regression models identified several significant predictors of student happiness, the Nagelkerke R2 values (0.194 and 0.103) suggest that a substantial portion of variance remains unexplained. This highlights the complex and multifaceted nature of happiness, which may be influenced by factors not easily captured through structured surveys, such as family dynamics, cultural identity, personal values, and emotional narratives. To address this, future studies should incorporate qualitative approaches, such as in-depth interviews or focus groups, to explore the subjective and contextual dimensions of happiness from the students’ own perspectives. Such methods could offer richer insight into how students define happiness, what challenges they face, and which aspects of university life they value most.

4.4. Implications of the Study

This study contributes to the growing body of literature on student happiness by contextualizing it within the under-researched setting of East Malaysia. It supports and extends cultural theories of well-being by demonstrating how institutional and communal variables such as safety, friendliness, and religious orientation play a critical role in shaping subjective happiness in collectivist societies. The findings underscore the need to incorporate cultural and environmental dimensions into models of student well-being, challenging the dominance of individualistic paradigms commonly seen in Western literature.

From a practical standpoint, the results of this study have immediate relevance for student affairs divisions and higher education planners in East Malaysia. For instance, ensuring a safe hostel environment and fostering a supportive atmosphere among university staff are modifiable factors that significantly enhance students’ happiness. These findings can inform campus-wide mental health initiatives, student engagement policies, and institutional development plans. Moreover, the results provide a local evidence base for guiding future well-being frameworks in regional universities, supporting targeted interventions in areas with similar sociocultural profiles. This highlights the importance of teaching basic communication skills as a crucial intervention that should be performed at the organizational level, as its benefits can have a more far-reaching impact on promoting organizational happiness compared to more expensive infrastructural investments.

5. LIMITATIONS

A key limitation of this study is the use of a non-validated measure of happiness. The outcome variable was assessed using a single binary-response item, which may not capture the multidimensional nature of happiness or its fluctuations over time. The use of a single-item measure to assess happiness also precludes calculation of internal consistency reliability, such as cronbach’s alpha. This limits the psychometric depth of the assessment and may reduce the sensitivity of the outcome variable. Furthermore, the UMS Happiness Index items were adapted from an earlier internal survey and have not been subjected to rigorous validity or reliability testing. This limits the generalizability and psychometric robustness of the findings, and future research should consider using standardized, validated instruments to strengthen construct measurement.

The high proportion of “unknown” responses for household income shows another limitation, likely due to students’ unfamiliarity with the term “B40” or limited knowledge of their family’s exact income level. Future surveys should provide clearer definitions or alternate proxies for socioeconomic status to improve data completeness and interpretation.

Although the sample size is large, the study focuses on a specific group in society, namely university students, so it is suggested that the Happiness Index be applied to populations involving different groups of society in future studies to verify the findings in a more representative population.

The study relied on self-report measures, which may have allowed participants to answer questions in a socially acceptable manner. The study only included undergraduate students from UMS. Future studies should include students from different levels, such as post-graduate, to demonstrate the validity of the findings. Lastly, future studies should include more variables to identify their correlations. This study did not include advanced model fit evaluations such as Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). While the Nagelkerke R2 and classification accuracy provide a basic indication of model performance, further statistical evaluation would improve understanding of the model’s discriminative capacity and comparative fit.

CONCLUSION

The results of the study show a significant relationship between students' backgrounds, particularly gender, religion, field of study, and happiness. The study also shows that the university environment contributes to students' happiness levels. Therefore, universities should invest in both facilities and communication skills training that have the potential to improve the quality of life among students. Students with a higher quality of life will produce better academic output and contribute to the improvement of university rankings. It is crucial that we address this issue rather than focusing solely on academic metrics.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: N.T.P.P. and V.C.T.: The study was conceived and designed; N.T.P.P. and C.Y.: Data were collected; N.T.P.P., V.C.T., and A.K.: Analysis and interpretation of the results were carried out; C.Y. and A.K.: The manuscript was drafted; C.M.H.: Supervision and validation were provided. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| UMS | = Universiti Malaysia Sabah |

| B40 | = Bottom 40% income group (Malaysian household classification) |

| COVID-19 | = Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| SPSS | = Statistical Package for the Social Sciences |

| OR | = Odds Ratio |

| ROC | = Receiver Operating Characteristic |

| AIC | = Akaike Information Criterion |

| BIC | = Bayesian Information Criterion |

ETHICS APPROVAL AND CONSENT TO PARTICIPATE

All procedures were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Malaysia, approval code UMS/Jketika2/2021.

HUMAN AND ANIMAL RIGHTS

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study, with approval for scientific article publication. Personal information will not be disclosed for confidentiality, and only research-relevant information shall be reported.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the first author [N.P]. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences of UMS, Malaysia, for their support during the conduct of this study.